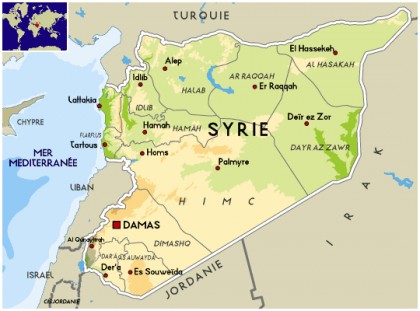

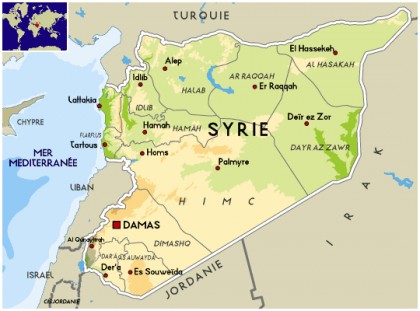

Deraa Why? Observers are wondering since the beginning, March 13, revolt in this town in south-eastern Syria. What specific economic or social unrest explain this sudden? The city has no political overtones, nor were militant past, and the Muslim Brotherhood are not very present. The various communities that make up its population have never had any specific demands.

The incident that set fire to the powder is that a group of students armed with chalk and wrote anti-government slogans on the outside walls of their establishment. Security forces have struck teenagers to stop them and take them to Damascus. Families are then gathered in the main mosque in the city to discuss the matter, but armed men attacked them by firing in all directions.

Called for help to treat the wounded, a doctor, accompanied by two nurses was greeted upon arrival at the mosque by a deluge of fire. He died while his assistants were injured. That's how the dispute began Deraa before spreading elsewhere in the country. Without the fierce repression by security forces, the incident might have passed unnoticed.

But it is clear that the Syrian security apparatus has a free hand to act as he sees fit. Can we say that the Syrian revolution is on? Probably. The process started is the one that led to the fall of the Tunisian and Egyptian. This is a spontaneous popular uprising, no outside hand, neither the Islamists nor other opponents in this tightly controlled country, has planned.

The dangers facing Syria are based on the response provided by the arrangements on this revolutionary thrust. If he remains on its security strategy by continuing to repress the population and stifle society, it will maintain stability in the apparatus of power. But this option could be difficult to hold, outside powers like the United Nations has set limits on the use of force against peaceful demonstrations.

The novelty is that the price of political and diplomatic suppression has greatly increased. The international community can exert pressure ranging sanctions on the embargo, passing through the freezing of bank accounts, banning travel of politicians or recourse to justice. In the case of Syria, the possibility of using the special tribunal investigating the assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri [in 2005 murder that Syria is suspected of masterminding] might embarrass some Syrian officials .

President Assad has chosen for now to avoid divisions within its authority by not taking initiative for real change and continuing to repress the demonstrations. But any international sanctions or condemnation would be a personal failure for the head of the Syrian state, which has managed with skill to restore the prestige of Damascus, which make it more and more foreign leaders.

The second option would be the distribution of social and economic benefits to regain popularity, as is often the rich Gulf countries, Algeria and Libya, and who buy their citizens. But it also requires resources that Syria does not, this strategy is less operative when she wants to meet political demands, especially when it comes after a bloody crackdown.

As the experience of the four Arab countries where revolutions have broken out - Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen and Libya - a reform policy proposed by the government after decades of refusal to make a radical transformation in the way to govern: it must build a relationship with the company that is not based on control, fear, repression, and grant all freedoms, but, above all, fight against corruption has become a mainstay of political system.

Any attempt to challenge corruption will be faced with powerful opposition capable of destabilizing the government. Remains an option that may tempt the regime, the most dangerous one to play the communal divisions, with the aim of terrorizing the citizens into believing that a relaxation of the iron fist would promote separatism and tearing of the fabric office.

The fear that Syria is divided on the Iraqi model could convince the public that only a dictatorship can guarantee stability and security. This logic must be clearly rejected by all Syrians. Their society is not attained by the virus of sectarianism or domestic conspiracy, and different communities have never opposed the country's modern history.

The first great Arab nationalist was a Christian, but especially today we see that among the intellectuals of the most respected and most credible calling for a democratic society, there are many Alawites (community to which the Assad belongs). The Syrian citizen who has lived in recent decades the terror of a tyrannical regime, would not replace it with fear of his own society.

This is the priority for the Syrian people, who yearns for another life. The author of the article, Bassma Kodmani, is director of the Arab Reform Initiative, a consortium of research institutes working on the transition to democracy in the Arab world.

The incident that set fire to the powder is that a group of students armed with chalk and wrote anti-government slogans on the outside walls of their establishment. Security forces have struck teenagers to stop them and take them to Damascus. Families are then gathered in the main mosque in the city to discuss the matter, but armed men attacked them by firing in all directions.

Called for help to treat the wounded, a doctor, accompanied by two nurses was greeted upon arrival at the mosque by a deluge of fire. He died while his assistants were injured. That's how the dispute began Deraa before spreading elsewhere in the country. Without the fierce repression by security forces, the incident might have passed unnoticed.

But it is clear that the Syrian security apparatus has a free hand to act as he sees fit. Can we say that the Syrian revolution is on? Probably. The process started is the one that led to the fall of the Tunisian and Egyptian. This is a spontaneous popular uprising, no outside hand, neither the Islamists nor other opponents in this tightly controlled country, has planned.

The dangers facing Syria are based on the response provided by the arrangements on this revolutionary thrust. If he remains on its security strategy by continuing to repress the population and stifle society, it will maintain stability in the apparatus of power. But this option could be difficult to hold, outside powers like the United Nations has set limits on the use of force against peaceful demonstrations.

The novelty is that the price of political and diplomatic suppression has greatly increased. The international community can exert pressure ranging sanctions on the embargo, passing through the freezing of bank accounts, banning travel of politicians or recourse to justice. In the case of Syria, the possibility of using the special tribunal investigating the assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri [in 2005 murder that Syria is suspected of masterminding] might embarrass some Syrian officials .

President Assad has chosen for now to avoid divisions within its authority by not taking initiative for real change and continuing to repress the demonstrations. But any international sanctions or condemnation would be a personal failure for the head of the Syrian state, which has managed with skill to restore the prestige of Damascus, which make it more and more foreign leaders.

The second option would be the distribution of social and economic benefits to regain popularity, as is often the rich Gulf countries, Algeria and Libya, and who buy their citizens. But it also requires resources that Syria does not, this strategy is less operative when she wants to meet political demands, especially when it comes after a bloody crackdown.

As the experience of the four Arab countries where revolutions have broken out - Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen and Libya - a reform policy proposed by the government after decades of refusal to make a radical transformation in the way to govern: it must build a relationship with the company that is not based on control, fear, repression, and grant all freedoms, but, above all, fight against corruption has become a mainstay of political system.

Any attempt to challenge corruption will be faced with powerful opposition capable of destabilizing the government. Remains an option that may tempt the regime, the most dangerous one to play the communal divisions, with the aim of terrorizing the citizens into believing that a relaxation of the iron fist would promote separatism and tearing of the fabric office.

The fear that Syria is divided on the Iraqi model could convince the public that only a dictatorship can guarantee stability and security. This logic must be clearly rejected by all Syrians. Their society is not attained by the virus of sectarianism or domestic conspiracy, and different communities have never opposed the country's modern history.

The first great Arab nationalist was a Christian, but especially today we see that among the intellectuals of the most respected and most credible calling for a democratic society, there are many Alawites (community to which the Assad belongs). The Syrian citizen who has lived in recent decades the terror of a tyrannical regime, would not replace it with fear of his own society.

This is the priority for the Syrian people, who yearns for another life. The author of the article, Bassma Kodmani, is director of the Arab Reform Initiative, a consortium of research institutes working on the transition to democracy in the Arab world.

- Demands of #Syrian Freedom Protesters #Syria #English #Arabic #French (04/04/2011)

- War Cycling Tour of Libya Suspended (17/03/2011)

- 'It is time for a change' (25/03/2011)

- EU condemns violence in Syria, urges reforms (11/04/2011)

- Le dernier refuge des histoires, du laisser-vivre et de la gratuité (07/04/2011)

No comments:

Post a Comment